Why did Abdullah have to die?

Last Friday, loved ones of 23-year-old Abdullah, a student of political science at Government Shaheed Suhrawardy College in Old Dhaka, gathered in a graveyard in Bardaanchara, a small village in Benapole, Jashore, to bury him. Abdullah was a vital part of the student-led mass uprising in July-August, fighting for justice, for change, and for a future he believed in. But instead of celebrating his victory, his family watched in agony as they buried him—three months after a gunshot to his head left him fighting for his life.

Why didn't he die that day? Why did he hang on, only to slip away after three months of suffering, three months of agonising hope that he would make it? These heart-wrenching questions will remain unanswered, but we cannot help but wonder: could timely medical intervention have saved Abdullah's life? Instead of a sombre burial, could we have seen him alive, his face lit with the joy of knowing that, despite the violence of those days, his cause had triumphed?

Abdullah was shot in the forehead on the evening of August 5, in front of Bangshal Police Station. This was the day the people's uprising, which he had passionately fought for, achieved an incredible victory. But victory came at a brutal cost. After being shot, Abdullah lay on the street for hours, bleeding, with no one to help him. It wasn't until someone rushed him to Mitford Hospital that he received treatment. From there, he was transferred to the Dhaka Medical College Hospital (DMCH), where doctors operated on him. After his discharge, however, his condition worsened, and he was hospitalised again. An infection had set in, and by the time he was moved to the Combined Military Hospital (CMH), it was too late. His prolonged fight to live ended on the morning of November 14.

In a recent speech, the chief adviser of the interim government mentioned that around 1,500 people had perished during the uprising. And 19,931 people were injured, many of them blinded, maimed or barely alive. How many of them, like Abdullah, are still fighting for their lives? And how many, despite the horror they endured, remain forgotten as the rest of us move on, distracted by the new headlines of the day?

Apart from the loss of eyesight or a limb, many have lost the ability to work, which has left them and their families under a huge economic burden.

A report by The Daily Star in October found more than 200 such patients in some of the major hospitals in Dhaka. The stories from these visits revealed the despair of these young people, who now face a bleak and uncertain future.

For instance, Mozammel Haque, 21, has lost vision in both eyes because of pellet injuries on July 18 during the quota reform protests in Narsingdi. His mother despairs about how he will sit for his exams or even find a job, whether he will ever get married or have a family.

Mohammad Sujon, 21, a cable TV operator, needed two open heart surgeries and another one in his intestine to stay alive after two bullets pierced his torso on August 5 in Old Dhaka. His family of four members is financially dependent on him. What are his prospects of working again?

As the days wear on and we go about our business, and go back to nursing our personal grievances, the faces of these brave individuals will start to fade. How easy it is to forget things that make us feel uncomfortable or events that don't really affect our lives. Have we forgotten so soon how horrific those days between July 15 and August 5 were? Have we forgotten what these young people have gone through, what families who have lost their loved ones in this uprising are going through? Have we erased from our minds those chilling footage of people, most of them young, being shot in cold blood, their bodies treated with utter disrespect, the blank expressions of the injured or dead being hurriedly carried by their friends?

Fresh news constantly flooding us with new fears and uncertainties is perhaps the reason behind the loss of short-term memory. Grisly murders, mob killings, frightening robberies, hours of traffic gridlock every time a disgruntled group decides to block the roads to get their demands met, food prices hitting the roof, worrisome international ratings about low economic growth, the weight of piling up foreign debt, and an uncertain political landscape—these are the items on our daily dose of stress factors. But they are also a wake-up call for us who thought that August 5 would magically erase 15-plus years of systematic looting and suppressing and maiming a nation physically and psychologically, so that they would lose the ability to stand up for their rights.

We must not forget that everything that is happening to us is a consequence of that dark period in history.

Which is why we must be clear about our priorities. We must prioritise the care of the injured—those who are now facing a future without sight, without limbs, or without the very life they once knew. There are around 400 people who have lost their eyesight, many of them students, as a result of bullet wounds and others who have critical injuries (such as serious head wounds) that require complicated surgeries, some of which may need advanced treatment abroad.

The government has set up a July Shaheed Smrity Foundation to provide support to the families of the martyrs and to those severely injured during the July-August uprising. While the interim government has waived treatment costs for the injured, delays and inefficiencies plague the system. Reports suggest that funds meant to help the injured have not been distributed quickly enough. The burden of costly medical tests and medicines, unavailable at public hospitals, falls on the families, while patients in private hospitals face crippling bills. Numerous patients are from other districts and from families who cannot really afford the cost of travelling to Dhaka, accommodation and food for those attending to the patient. These costs have to be taken into account while disbursing funds.

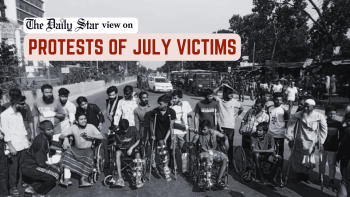

On November 13, injured protesters gathered outside the National Institute of Traumatology and Orthopaedic Rehabilitation (NITOR) and the National Institute of Ophthalmology, their faces filled with frustration and despair. The apparent slow response to their needs had forced them to take to the streets, demanding the care they had been promised. In response, four advisers visited the protesters late into the night, acknowledging the government's shortcomings and pledging immediate action.

Swift, decisive action must follow these promises. The government must ensure that the funds for the treatment of the injured are adequate and reach them on time. Many of the injured have still not been included in the list; this must be done urgently. Donations and assistance must come from the public as well. Already, individuals and small groups have begun to offer assistance, but it is not enough. Those who will be released from hospital must be given the support needed for their rehabilitation. We must all work together to help those who have given so much, to rebuild their lives with dignity, knowing that their sacrifices will never be forgotten or undermined.

Aasha Mehreen Amin is joint editor at The Daily Star.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments