The Birangona in poetry and conversation

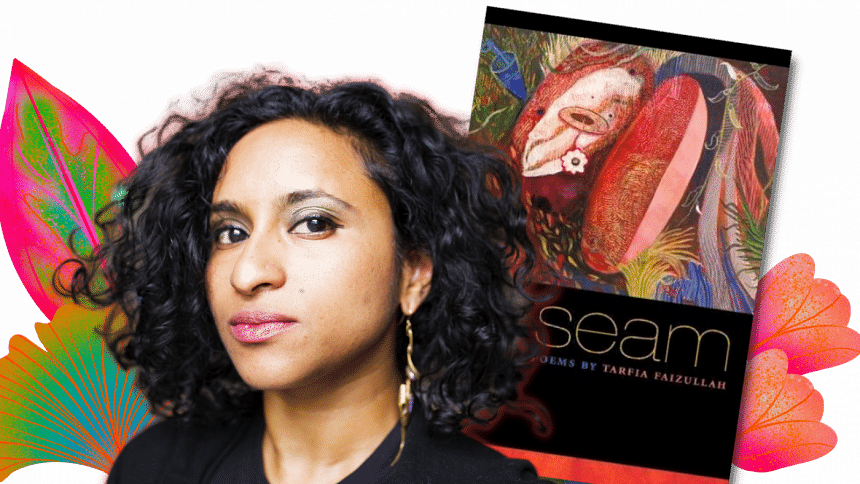

Tarfia Faizullah is an artist and poet, born to Bangladeshi immigrant parents in Brooklyn, New York and raised in Texas. While her poetry has won three Pushcart prizes and been presented in the Liberation War Museum of Bangladesh, the Library of Congress, the Smithsonian, New York University, Barnard College, University of California Berkeley, and the Poetry Foundation, among other places, some of her most powerful verses were conceived from a need to imagine the experiences of the two million women who were raped by Pakistani army during the Bangladesh Liberation War. Using a Fulbright fellowship, Tarfia decided to come to Bangladesh to research the war and interview the women whom the Bangladesh government, in 1972, titled Birangona (war heroines). These interviews resulted in Seam (Southern Illinois University Press, 2014), Tarfia's debut collection of poems which won the Crab Orchard first book prize.

In this conversation with Sarah Anjum Bari, Books and Literary Editor at The Daily Star, Tarfia Faizullah discusses her art, her inspiration, and her experience of interviewing Birangona women.

Your book is full of silences–the things you or the other people speaking don't share in great detail–but it's also about transparency. For instance, you reveal the questions you asked the Birangona women. Why?

Partly because I'm a writer and I see the world as contradictory. So, even though there's peace there is also war. Even though we keep experiencing in history genocide and rape, there is always an attempt to say–look at these things so it doesn't happen again but then of course it does. For me, the balance between silence and transparency is a way of getting at that contradiction, that there are a lot of women who never come forward about the violence that has happened to them. The book is an attempt to capture the importance of listening to those voices that are willing to speak and also listening to the silence of the women who are not able to for understandable reasons.

You started out writing the poems from imagination and then decided to speak to the women to avoid fetishizing them. How did the poems change through these two approaches?

I would say that it was more of a confirmation than a rewriting. What did change was the thinking of these women as part of a community and having sisters or lovers. I was lucky to interview a number of women together in Sirajganj and I realised their experiences are interconnected–they affect the individual and then the family, the community and then the country. Of course I was born and raised in America so I have more of an individualistic perspective, but I was also raised in a Bangali household, so I understand that shongshar for example is a profound unit.

One of the criticisms of my book was that these poems are too beautiful; how can these women happen to speak so beautifully? And I thought–what tells us that a woman who has experienced violence is not capable of beautiful thoughts?

One of the women I talked to said to me, Onek manush ashchhe proshno niye. Apni ki korben apnar kolom diye? 'A lot of people have come to us with their questions. What will you do with your pen?'

Did this question impact your writing?

Yeah. The whole reason I applied for a Fulbright was because I was writing these poems from imagination and I thought, these women are still alive, it's actually not right for me to continue writing these without at least trying to speak to them. Which to me meant that I wasn't just writing about myself or my feelings, I was writing with a greater responsibility. Her question just increased and emphasised to me what I was doing–I really wanted to try to get it as right as I could, even though my Americanness and my having never gone through those experiences are obvious limitations.

Tell me more about the interviews. How many women did you speak to and how did you get them to open up about their memories?

I was lucky enough to interview Ferdousi Priyabhashini before she passed away. There were maybe 8-10 women that I interviewed in Sirajganj. I interviewed a family of sisters who had all been raped and I also met a woman who was not able to speak because she's very ill–I met her and her daughter. I went to Sirajganj because there was this woman who was a freedom fighter and she runs a retreat for women who were victims during the war.

I don't think it was that I got them to open up, it was that for their own reasons they decided to open up to me. I didn't want to press the issue; I don't have any journalism expertise, I'm a poet and artist. So I felt very cautious. I started out light, let them get to know me first. The woman who runs the retreat in Sirajganj gave the green light also, so it was about her letting me into that space. I had an incredible experience with a family of sisters that I interviewed, and I was speaking with one of the sisters and the other sister came up behind me and started playing with my curly hair. She said to me, bechara, you probably don't have anyone to brush your hair for you!

There was another woman who had dementia. It was very painful and moving to realise that the mother was not in reality, but that her daughter was very aware of what her mother had gone through and she felt the importance of sharing that.

So it didn't feel like an interview, it felt like an exchange.

How did you decide what you wanted to ask them?

I was curious about the emotional experience because that's often what gets lost amidst nationalism and politics. I mainly wanted to know about their inner lives. Most of my questions were less intellectual and more emotional.

As a poet working on a creative project and not, as you said, as journalist, what do you think are the ethics of interviewing the survivor or a victim of sexual assault?

I did not write a perfect book. I think that what I wrote is problematic but what happened to these women is more problematic. As an artist who is trying to get across human trauma–especially trauma that is, as in the case of the Birangona, state-mandated and systematic violence–I know I failed a lot. I think that if you're an artist and you want to take on difficult material, then your intentions matter. The willingness to fail matters.

I also did a lot of research on the psychology of trauma even though I'm not a journalist. I read a lot of interviews and how journalists approach these subjects. So I don't think being an artist means you can do whatever you want, it means: educate yourself and make choices that are thoughtful.

Did the project impact the writing that you did after finishing this book?

I realised that I really care about women's voices. So in my second book, Registers of Illuminated Villages (Graywolf, 2018), I have a sequence of poems about a village in Bangladesh that used to be called Sowabpur and it used to be called the village of love, but then became the village of widows because the Pakistani army went into that village and killed every single man and left the women. I wrote poems from the perspective of those women.

Bangladeshi women specifically really matter to me because there is a history of silence and a history of women silencing themselves. I became more aware, too, of the responsibility as an artist.

Why are sounds so important to you as a poet?

Sounds have meaning. One of the great things about poetry is that it's available to the illiterate–it's a very radical and democratic art form in that way. It's why it's used in political slogans for example. It's not just the meaning of the words but the effect of the sounds. Poetry lives in this interesting world between nonfiction and music, between music and fiction. Because I'm a poet, that's part of my toolkit–thinking about how to get across concepts like obsession, nostalgia, history and memory in musical form.

What is your relationship with Bangla poetry? Where would you place your work in the lineage of Bangla poetry, particularly those that came out of the Liberation War?

I wish I was fluent enough to write in Bangla–I read and understand Bangla but I'm not as well versed in very complex Bangla. But I care about Bengali poetry a great deal. My mother and I just went to a dance recital of one of Tagore's stories and I've been reading his biography and a lot of his poetry. I also care a great deal about Nazrul Islam. But I was just saying to my mom that you don't hear as much about women poets. I think there must be a woman who was writing at the same time as Tagore and Nazrul and just didn't get the same kind of attention that she deserved. I have a future hope to learn more about Bengali women poets.

My job is to write the poems that I want to write and get them out into the world. Outside of that, I try not to comment too much on how or where I should be talked about.

What other subjects are you passionate about as a poet? Do you have any favourite Bengali women writers?

Right now I'm working on a poetry collection that is focused on immigration and the Bengali immigrant's experience in America. I'm a perfectionist, so lately I'm trying to allow my poems to be imperfect and capture imperfection. I don't want to think of myself as morally superior, so I'm trying to think about how you allow for a flawed but very human perspective. And also, I hate to admit this, but bhalobasha! I don't have any authority on it but I have this idea that my third book is a love letter to somebody who doesn't know that he's meant for me.

We're in an exciting moment in American poetry where there are more and more deshi voices coming forward. Some Bengali contemporary writers I'd like to shout out to are Shabnam Nadiya, Seema Reza, Chowdhury, Anuradha Bhowmik, Fariha Roisin, Tanais, Sharbari Zohra Ahmed, Promoti Ilam, Ashna Ali and Amatan Noor.

Do you think your art serves a purpose?

You're asking some very difficult questions! If I think too much about the function of art it just falls apart very quickly. When you're working on it, you don't know if it's going to affect anybody else. But my life really changed because I started thinking about these women and writing these poems. For instance, despite me resisting the criticism of Seam being too beautiful for the subject matter, I do think I have become a less lyrically beautiful writer in some ways.

I do think that art has a function, it is not just necessary but essential. Art is where you see the human spirit, what we would call the soul; it's an important place to find, recover and discover your own humanity.

Sarah Anjum Bari is Editor of Daily Star Books and Star Literature. Reach her at [email protected] and @wordsinteal on Twitter and Instagram.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments