The old and new Bangladesh from the eyes of a historical fiction writer

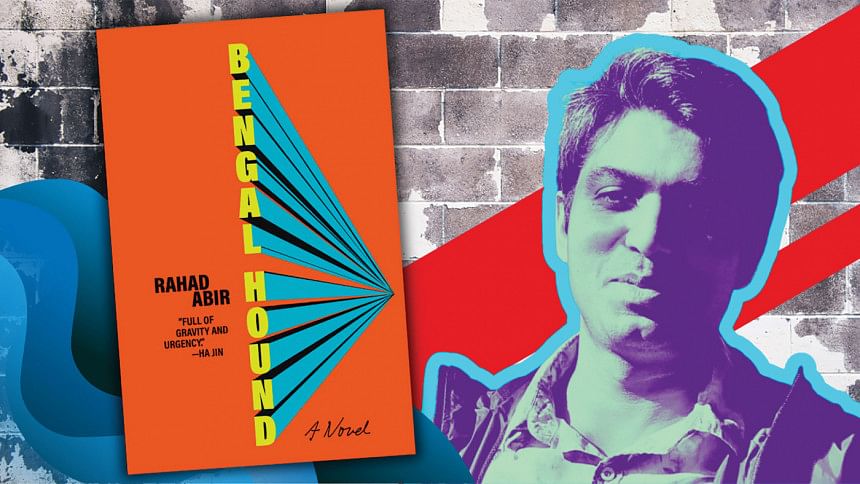

When I first came across a review of Rahad Abir's novel Bengal Hound in The Daily Star, I was intrigued by the storyline: A Dhaka University student in 1960s East Pakistan eloping with his love amidst political upheaval and protests that pave the way for independence.

Given the recent student protests in Bangladesh, I was curious to learn about the 1960s protests but told through a fictional story–what was different or similar?

Winner of the Georgia Author of the Year Award for literary fiction, Rahad Abir builds a world and characters that provide deep insight into the impacts of Partition and subsequent divisions of Bengal. He has a Master of Fine Arts in fiction from Boston University and is the recipient of the Charles Pick Fellowship at the University of East Anglia and the Marguerite McGlinn Prize for Fiction.

Recently I sat for an interview with the author on behalf of The Daily Star.

Thank you for writing this captivating story and sharing some of Bengal's history with the world, for not too many people know about it. What is the genesis story of Bengal Hound? How did the concept of the novel come to you? What inspired you to write it?

I grew up reading Bangla classics—devouring the works of Bankim, Sarat, Tagore, Tarasankar, Bibhutibushan, Manik, among others. I also began writing in Bangla. For most of my writing life, I have been intrigued by the history of India's Partition, the pre-Bangladesh Pakistan era, and the never-ending Hindu-Muslim conflicts in South Asia. While many novels cover the 1971 War of Independence, only a handful explore East Pakistan's turbulent and chaotic years of the late 1960s that led to the creation of Bangladesh. When I decided to write a novel, I wanted to specifically focus on the mass movement in 1969.

Bengal Hound is inspired by a family lore. In the early 1960s, my grandmother's sister ran away with her boyfriend on her wedding day, only to be murdered by her family members shortly afterward. The family lore says that her dead body was thrown into the river. I wanted to place this tragic love story at the heart of my novel.

What did your research for this novel look like and how did you go about incorporating your findings? Were there any ethical considerations you made?

I started writing this book in 2014, planning to finish it in two years, but I ended up spending about eight years working on this novel—revising, rewriting, reworking it again and again. I don't call the book a historical novel; rather, it is a work of fiction largely based on historical events. My source materials are obviously derived from history.

For my research, I initially tried to read history books, but I found the writing of most history books boring and uninteresting. I began reading memoirs and nonfiction books about the same time period as my novel, and that worked for me. To me, reading memoirs is like reading someone's diary. When we write in our diaries, we open up and become nostalgic, sharing our personal stories and emotions. As a fiction writer, I am more drawn to this kind of narrative. I also checked out photographs from the 60s to get a sense of the time and place.

What do you find are the biggest challenges of writing historical fiction and how did you navigate those for this particular novel?

I think it is incredibly difficult to create a work of fiction that is both historically accurate and engaging. Keeping the plot consistent, tracking characters' ages, and aligning personal stories with historical events requires a lot of effort. Even moving a scene by a week or a month can affect the entire timeline, so I had to be very careful with dates, events, and years. Patience is essential. The novel took me about eight years to complete, though I finished the initial draft in less than two years. The rest of the time was spent editing, revising, refining, and adjusting the narrative within the context of historical events.

Although you wrote the novel in English, the essence of Bangla and Bengali culture emanates from your storytelling. Would you be able to speak to your experience using the English language to immerse readers in a very particular cultural world? What are the advantages and disadvantages and limitations?

I always say that I write Bangla in English, because I started writing in Bangla and then switched to English. To me, this transition is just the continuation of my writing process; what I used to express in Bangla, I now express in English. Something, however, always gets lost in translation when moving between cultures and languages.

I believe being a bilingual writer is a big advantage. I grew up in Bangladesh and spent most of my life there, which probably gives me an edge over other Bangladeshi Anglophone writers who didn't have the same experience or can't read or write in Bangla. I think being bilingual helps me represent my home culture more authentically.

If I have to talk about limitations, I will say that, like any language, Bangla has unique words, phrases, and sayings that are difficult to express in English. We writers do our best, but translations often lose the original flavor and essence of the source language.

Many of the characters in Bengal Hound are grieving, and you explore their grief with the backdrop of political upheaval. Would you be able to speak to your experience writing the journeys of grieving characters, especially given that grief is not always linear?

Interestingly, I didn't do all of this knowingly. I was writing the characters and the characters led me into their lives. They told me their own stories. One reason grief appears in many forms in this novel is that the Partition of India is a significant event that still impacts the lives of people on the Indian subcontinent.

For Bangladeshis, it's more than that. First came the Partition, then Pakistan, and during that time, there was the unholy trinity between the Punjabi-backed government and the people of West Pakistan and East Pakistan, which ultimately resulted in the creation of Bangladesh after a bloody war in 1971. The Bengali people in Bangladesh went through a great deal. In the span of 25 years, from 1947 to 1971, a lot happened. Lives changed tremendously. First, you were a citizen of India, then Pakistan, and finally Bangladesh. That's a lot to experience in one lifetime. Naturally, the geopolitical and political changes had enormous impacts on the lives of people, including psychological impacts. How do you expect them to act normally? That's an abnormal expectation, isn't it?

Your recent essay in Shuddhashar: FreeVoice draws interesting parallels between the 1960s student protests to the recent ones in Bangladesh. You write that 'history repeats itself,' prompting readers to reflect on the patterns that feed oppression. What do you see as the role of literature, particularly historical fiction, in responding to present-day issues?

Quite interestingly and surprisingly, Bengal Hound is very relevant in light of the recent political upheavals in Bangladesh. The novel captures the mass student protests of 1969 against the Ayub regime in East Pakistan which led to Bangladesh's independence in 1971. The recent student protests in Bangladesh, which ended on August 5 with the overthrow of Sheikh Hasina's 15-year dictatorship, are regarded by many as a second independence. So, though the setting and characters are different in Bengal Hound, the underlying theme is the same.

Philosopher Hegel once said, "One thing we learn from history is that we never learn from history." I believe literature, art, and music help us understand who we are as humans. By studying a country's literature and art, you can better understand its people. But do our politicians care to learn from history? Not at all.

Would you be able to speak to your experience writing about Bangladeshi and Bengali characters as a person of diaspora?

In the summer of 2012, I began writing in English. There are many Bengali authors I admire whose works are equally outstanding as those of many literary giants in English and other European languages. Unfortunately, because they chose not to write in the language of their colonizers, many of the best Bengali authors remain largely unknown to the world. My decision to start writing in English was primarily motivated by this factor. As I mentioned, I write Bangla in English. And writing in English enables me to respect the traditions and cultures of my home country while also understanding the enticements and expectations of a global audience.

As a writer from the Bengali diaspora, what are your hopes for Bangladesh?

In the West, South Asian literature is primarily dominated by works from India and then Pakistan. This dominance has made it difficult for Bangladeshi authors to receive the attention they deserve for their work. Also, not many Bangladeshi writers write in English, and there are still few English translations of Bengali literature from Bangladesh. I hope that in the future, Bangladesh will be seen not just as a nation plagued by corruption, political violence, or natural disasters, but as a country rich in new literary voices and young talent across all fields.

Sumaiya Matin is a Bangladeshi Canadian writer. To follow her work, visit www.sumaiyamatin.com.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments