Why stock market is going nowhere

Designated as a basket case after gaining independence in 1971, Bangladesh silenced even its harshest critics as it transformed into one of the world's foremost development cases.

Born as the second-poorest nation in the world, the country defied the odds to reach lower-middle income status in 2015 after making significant strides.

For example, poverty declined from 44 percent in 1991 to just around 5.0 percent in 2022, according to the World Bank. Literacy rates and access to electricity also skyrocketed while the country's gross domestic product ballooned from $8.7 billion in 1971 to over $450 billion now.

However, the country's stock market, full of poor performing companies that display limited growth, never matched that narrative of development. A lack of accountability in the secondary market, where irregularities are rife, took the shine off the exchanges further.

Given the situation, general investors almost never got the returns they expected. Instead, they often lost funds due to rampant manipulation of share prices of weak companies.

Even if they invested in the 15-20 well-performing stocks, capital gains were very limited as the share prices of such companies remain in the same range year after year amid floor price mechanism. Investors got good dividends, only from 1 percent of the total companies.

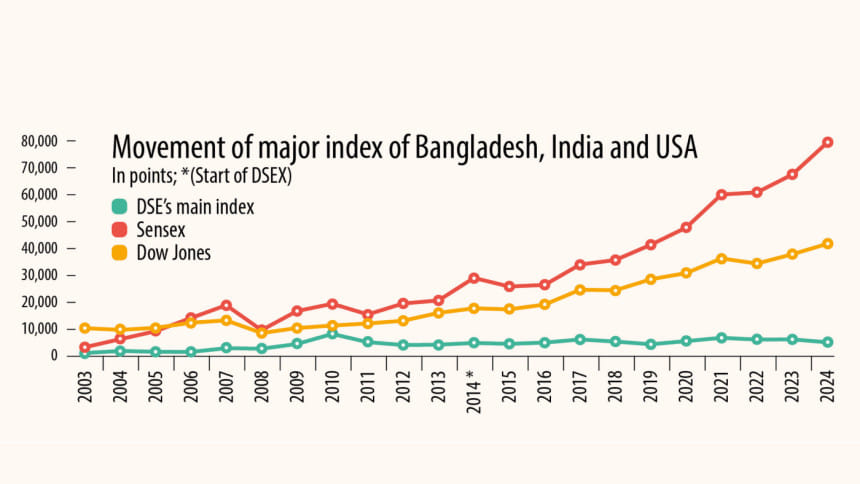

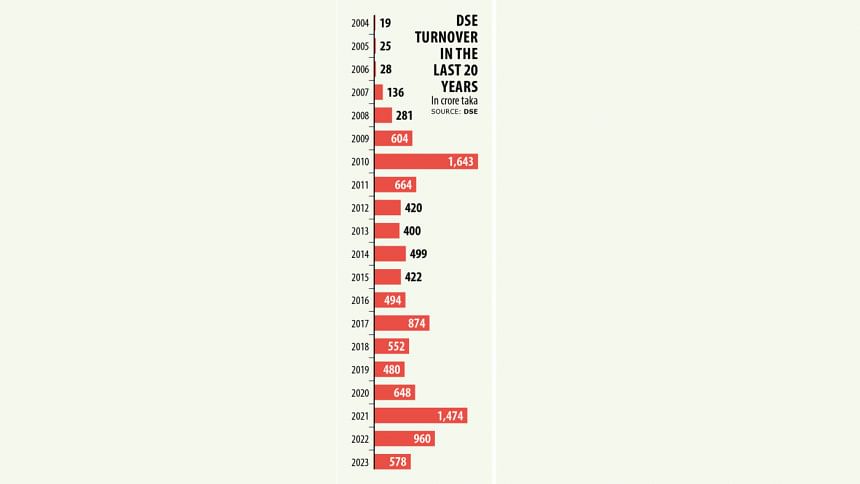

The stagnation of the stock market in Bangladesh is clearly reflected in the data.

Major indices in the USA, India and many other countries have been moving in a steady upwards trajectory despite some shocks from time to time and are currently hovering near all-time highs in terms of points.

However, the benchmark index of the Dhaka Stock Exchange (DSE) has not even hit the heights of 2010, when it soared to a record high of 8,918 points.

In short, over the past 14 years, the market has been unable to muster enough strength to cross its previous highest position as it would not be supported by companies' earnings.

Due to the slow growth of listed companies, the stock market index in Bangladesh has limited scope to rise, according to Mir Ariful Islam, managing director and CEO of Sandhani Asset Management Company.

"That is why the index remains in the same range while major indices in other countries rise year after year."

Among the 360 listed companies, around 23 percent, or 82 companies, are now junk stocks, DSE data showed.

In the past 14 years, 127 companies got approval to launch initial public offerings (IPOs).

Of them, only 45 remain in the 'A' category. A total of 35 were downgraded to 'B' category while a majority, 47, were relegated to the 'Z' category, commonly called the junk category.

The low number of quality IPOs is the main reason for the lackluster nature of the market, Islam added.

He also pointed to misrepresentation in financial reports for a loss of confidence.

"Many companies present financial reports that are not credible. So, investors are not attracted to them although their price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio ranges from the low single digits to 11," he said.

The P/E ratio measures a company's share price relative to its earnings per share. A high P/E ratio could mean that a company's stock is overvalued or that investors expect high growth rates.

Conversely, a low P/E can indicate that a company is undervalued or that a firm is doing exceptionally well relative to its past performance.

In countries like India and the US, even when the major indices rise, the P/E ratio falls, indicating that listed companies are growing heavily, supporting the rise in the index, he said.

He added that there were little incentives for good companies to get listed.

"There is no bar on borrowing from banks, so good companies do not need to go to the stock market. Tax incentives are not even a consideration as tax evasion is common," Islam added.

A medley of lost investment, false promises from the government, and low financial literacy has repeatedly prompted many investors to take to the roads in protest time and again after a plunge in indices.

Although it is uncommon to see investors of any stock market in the world protesting on the road solely due to a market crash, such scenes have unfolded repeatedly in Bangladesh.

The first such procession in the country's history was held in 1996, following the first major crash.

Since the start of the year, the share price index of the DSE had jumped a remarkable 337 percent by November 5, 1996, rising to 3,648 points.

One company, whose shares had a face value of just Tk 134, saw prices exceed Tk 18,000 per share that year.

However, the market began falling the day after, shedding 233 points following the day's trading session on November 6.

It had fallen to 957 points by April the following year. By May of 1999, the stock market was almost back to square one, plummeting to 462 points.

The next procession was staged in December 2010, following another similarly devastating crash.

But over the past 14 years, such protests have become commonplace.

A historic crash at the US stock market had a widespread impact on the whole world in 1929, costing people billions within a few days. The shockwaves of that blow ultimately sent the world into a period that has gained notoriety as The Great Depression. The US also saw a massive fall in its stock market during the financial crisis of 2007-08.

But you would be hard-pressed to find any newspaper clippings about any procession or protests being held due to those crashes.

The Amsterdam stock exchange, considered the oldest stock exchange in the world, has also never seen protests from investors despite crashing several times since 1602.

In Pakistan, small-scale protests were seen in 2005 due to the fall of the index. But such incidents were not repeated when the market later plunged to its lowest level in many years.

So, the question arises: Why do investors in Bangladesh protest on the roads after deciding by themselves to make trades on the stock market?

Abu Ahmed, a stock market analyst, said protests were not about the fact that indices go down, rather it is due to them not bouncing back afterwards.

In other countries, indices eventually rally after falling for any due reason.

Market indices have not risen here, but, at the same time, the PE ratio has not fallen as it should have in line with the growth of income of the listed companies, he said.

In the past five years, the DSEX, the benchmark index of the DSE, remained stuck to around 5,100 points. Its PE ratio has also remained static at around 11.

The S&P 500 in the US almost doubled in the past five years, but the PE ratio dropped to 26 from 33, indicating that the companies' earnings were rising at a faster pace than stock prices.

However, the irony is that investors in Bangladesh cannot even make money by holding on to good stocks.

"So, their frustration boils over following any big fall in the index."

This frustration with the market is reflected in the receding number of beneficiary owner accounts, which halved to 16 lakh in the past seven years, according to data from the Central Depository Bangladesh Limited.

Curiously, investors who held shares in good companies, which provided at least 50 percent dividend in their last financial year, incurred losses in the first six months of 2024.

On the other hand, people who bet on poor-performing companies, which declared less than 15 percent dividend, saw their portfolios puff up, an analysis by The Daily Star found.

Ahmed added that although investors protest frequently here, their demands are sometimes incoherent.

"They can demand relevant things such as lowering tax rates, exempting taxes, or they can raise the issue when a listed company does not follow its own disclosure. But the demands should be voiced through a press conference. Protests on the road do not look good."

Shakil Rizvi, a former president of the DSE, said many people took the stock market as their main source of income in 2010. So, a listless stock market was proving to be very painful to them.

He said that the usual suspects may have low stakes in the market, but they are objecting on behalf of the real investors, who usually do not take to the roads.

He added that although such protests may scare off new investors from the stock market, many of the demands raised were logical.

"Policies are changed frequently. Investors cannot say what changes may come the next day. This is not supportive for an investor," Rizvi added.

For instance, the National Board of Revenue imposed a capital gains tax of up to 40.5 percent. It was zero last year.

This sudden move led many to voice concerns. Finally, the revenue authority relented, but only to a degree. It reduced the maximum rate to 20.25 percent.

This is just one of many examples of change in policy that has spooked investors.

Take the case of Titas Gas, for example.

Without any prior notice, in 2015, the Bangladesh Energy Regulatory Commission (BERC) cut the fee Titas charges to distribute lines. As a result, the utility company lost more than Tk 3,000 crore in market value over a period of five months, with foreign investors seeing massive erosion of funds and left with no choice but to sell their shares.

In 2018, the same kind of intervention was seen in the Grameenphone, which was the largest listed company at the time.

The telecom regulator abruptly declared Grameenphone an operator with Significant Market Power (SMP) to enhance competition in the industry. This move led to additional restrictions and regulations on the company while conducting business operations.

The list goes on.

In fact, the Bangladesh Securities and Exchange Commission (BSEC) itself started to intervene in the market by extending the tenure of mutual funds.

On September 16, 2018, the BSEC extended the tenure of closed-end mutual funds by 10 years following calls from some asset management companies.

At the time, some funds were due for liquidation in a year or two. This meant that investors who had waited for nearly a decade to see returns would be forced to wait another decade to see anything.

Another example of the BSEC's intervention was the decision to impose floor prices, which dictated the lowest price that could be paid for a certain share.

Rizvi added that many of the companies that were listed on the stock market over the years are growth-less. "When the companies were close to shutting down, they came to the stock market," he said.

"So, the stock market remains sluggish year after year while rallying in other years. If investors hold a stock for years in India, they can earn huge sums."

As there is little accountability in the market, when investors lose funds, simmering discontent prompts them to agitate on the roads, he added.

Additionally, the stock market in Bangladesh is rife with gossip and manipulation. Resultantly, good stocks do not perform well while weak companies dominate, which is an uncommon scenario around the rest of the world.

Given the speculative nature of the market, general investors often flock to stocks based on hearsay looking to make a quick buck. Instead, they end up losing their funds.

Meanwhile, rampant manipulation erodes investor confidence further.

It is common to see poor-performing or junk stocks in the top gainers' list or at the top of the turnover list. This makes it seem like such junk stocks are promising. So, people rush to buy them despite the high degree of risk, which ultimately makes the market drier for well-performing stocks.

In the past, the BSEC has investigated manipulation, but has often handed out light punishments to wrongdoers.

Given the lack of strong deterrents, those with ulterior motives are encouraged to game the system.

Md Moniruzzaman, CEO of Prime Bank Securities Ltd, said the history of the Bangladesh stock market is painful as general people saw their funds go up in smoke year after year.

However, looking at the historic performance of other stock markets in the world, you will find that they generated profits for their investors most of the time.

For instance, the US market has recovered from a crash due to the financial crisis and also successfully weathered the storm brought on by the Covid-19 pandemic around a decade later.

Aside from these blips, it showed positive momentum most of the time.

So, why did the stock market in Bangladesh not rally?

"Because the market is full of junk stocks and poor-performing companies. At the same time, dividend payments are low. So, frustration among investors is high in Bangladesh," Moniruzzaman said.

Another problem he mentioned is that general investors in Bangladesh are highly speculative and aim to live out rags-to-riches fantasies by making money overnight.

"On the other hand, our regulator's activities also instigated them to protest. For instance, the regulator claimed several times that the market index was not overvalued. So when it dropped, investors blamed them."

Since the regulator portrays the rise of the indices as their success, people hold them accountable for any drop, he added.

In Bangladesh, the emotional spillover from such drops can have far more devastating impacts than protests. There have been reports of a few investors committing suicide after allegedly incurring huge losses while others suffered heart attacks.

"This is because our retail investors are too involved in the stock market, meaning most of their funds are invested in the market. Sometimes, they borrow from others to invest in risky products," said Ershad Hossain, managing director and CEO of City Bank Capital.

As product knowledge among general investors is poor in Bangladesh, our traders face huge pressure when the market drops. However, they have no option but to bring in investors as they are often working to fulfil a quota.

Margins are another big shock for the market as it is tough to make money after paying 14/15 percent interest on margin loans.

"The stock market is for institutional investors. Small investors normally go to asset management companies. However, our retail investors go to the stock market even if they do not fully comprehend the risk of products," Hossain added.

A top official of a brokerage firm, preferring anonymity, said protesters served a purpose for several parties several times.

Ataullah Naim, president of the Bangladesh Pujibazar Biniogkari Sommilito Porishod, said: "Bangladesh's stock market cannot perform better due to the absence of good companies. Additionally, institutional investors do not behave professionally so investors do not trust them.

"If you look at why the Indian stock market advanced, it was mainly because it has many listed growth companies and there are many professional fund managers whose performance is excellent. So, even housewives keep their savings in mutual funds."

On the other hand, our retail investors spend most of their savings in the equity market, often even by taking loans.

"So, they feel a huge shock when the stock market falls," he said.

"Actually, no government in Bangladesh has taken ownership of the stock market. So, they make many decisions against investor interests. As a result, investors protest on the road."

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments