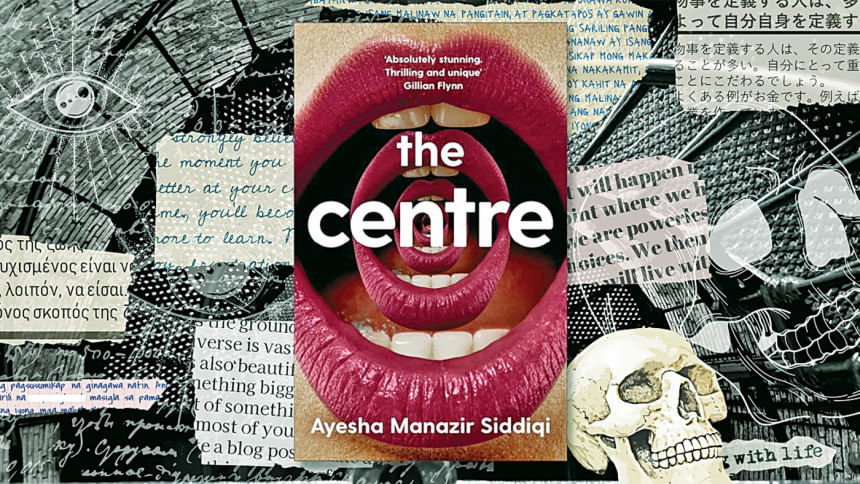

The occult thrills of ‘The Centre’

Rarely does a book arrive, a debut no less, that feels as inventive and accomplished as Ayesha Manazir Siddiqi's The Centre. Her novel is built on the crossroads of interpretation and ownership, of the power of language and of those privileged enough to reclaim it. In this regard, Siddiqi's novel is a contemporary reckoning of our often tenebrous relationship with the others' tongue. Unfortunately, the novel's all too visible flaws also cloud much of its muster.

Anisa Ellahi, an unremarkable subtitler of Bollywood films, meets Adam, a polyglot, at a seminar on "Translation verses Adaptation". She is fascinated with the many languages he seems to know, which is a stark contrast to his otherwise mediocre personality. As they begin to date and their relationship progresses, Anisa invites Adam to her home back in Karachi and Adam, to impress her, becomes fluent in Urdu practically in days. Refusing to believe Adam's obviously untrue excuses, she is made aware of the Centre's existence—a secret, invite-only, language-learning centre which claims to make its learners fluent in 10 days. Wishing to better her career, Anisa enrols for German with Adam's recommendation. Yet, as she gets involved in the Centre, she is slowly immersed into the organisation and its dark secrets.

Siddiqi's novel, so far, is tantalisingly smooth. In Karachi, we see Anisa's family parading around the urdu-speaking white boy to their friends and how a shopkeeper, upon noticing Adam's urdu, had "shook his head and spoke at length about what an honour it was to have someone from the west learn our language". These are instances where the novel excels most. The vestiges of such colonial humiliation and our modern-day co-opting of these are shown with great humour. Yet, at the same time, the story takes some jarring turns, which seem unnecessary in the first place. When Adam explains that he had to give up his phone while at the Centre.

Anisa asks, "But you texted me loads…", to which Adam explains that it was his friend Brian who replied to her texts. But won't a couple, who have been with each other for a considerable amount of time travel to meet one's parents in Pakistan, see through this?

A great deal of why the novel was partly an unpleasant experience for me was down to the author's insistence in commentary through her narrator. While her anxieties are relevant and, above all, true, they come packaged with the smell of complacently "aware" rich people, the "trustafarians" in the author's language, who have the the luxury to be aware and duly stop short of making any structural change or change in their behaviour beyond this awareness, rendering this generosity meaningless. When Anisa lies to her best friend Naima about the real cost of attending this elite Centre (because the latter comes from a poor background), she recognises what she has done and says: "Maybe, through these small erasures, which we tell ourselves are 'polite' or whatever, we're covering up a vast network of structural inequality." But what is the point of owning up to this, when she continues with the lie? Anisa's narration, on the whole, veers on the cloyingly casual (one could easily edit out the numerous "whatever" and "stuff"—filler words I fail to see as being part of Anisa's voice). It is remarkable that a book on how the elite often use language to bar or play on the disadvantaged (in the later chapters of the book, the readers would see how literal that is, in the case of the Centre), can itself be a subtle example of this.

Siddiqi's clever premise also does not go much beyond the vagueness of the Centre's all-encompassing power, which for all its plans of world domination, does not explain how it intends to do this with merely language labs. Arjun, one of the founders, even says, "We have the best scientists overseeing the process, neutralising all potential toxicities." Yet the book shows all of them working in their house, akin to a DIY project. Anisa's swift infiltration into the Centre, too, is worryingly unbelievable. Her chemistry with Shiba, who runs the Centre, undoubtedly works but one wonders here too how unrealistic and suspiciously convenient this is for the story.

Siddiqi's novel is quite enjoyable when she deals with the politics of the text, when instead of numerous pages of Anisa's boring complaints about her friend's relationship, we see more of the "magic language school," which I presume is what readers are really interested in. The novel is full of great lines such as "And prayer, I think, can be a bit like translation. There's a cosmic geometry to it." Or, "Did you see their faces when you said that thing about translation as colonialism? They were practically salivating. You're basically a dominatrix now."

The Centre, discounting some of its weaknesses, is smart, fresh, and full of suspense. Siddiqi and her debut novel deserves all the attention and perhaps more.

Shahriar Shaams has written for Dhaka Tribune, The Business Standard and The Daily Star. He is nonfiction editor at Clinch, a martial-arts themed literary journal. Find him on twitter @shahriarshaams.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments