Dhaka: A distant dream

"Desher maya tyag kore bideshe chole gechhen apnara?" ("So you have forgone your longing for the country and settled abroad?") It wasn't a question, but an attempt to understand a decision that was incomprehensible to him. His words gave away his emotions, which showed hints of scepticism, resigned curiosity, and even attempts at acceptance, but mainly disappointment. As a forest ranger, his work was to protect and preserve the country's emerald pride, the Sundarbans, and its rapidly vanishing wildlife, which became the nucleus of his existence. He had given his life to safeguarding a national landmark, he would live and die by it, and the impossibility of leaving a land that he had offered himself to, which in return had given him his livelihood, stories, passion, and faith, showed his sadness at our decision to move away from our magical country – mayabi desh.

Dhaka is a dream, albeit an elusive and distant one. Within minutes of landing, I'm embraced by an overwhelming feeling of belonging. I am welcomed by chaos, one that has been sown into the very fabric of my being. In fact, I slip right back into the chaos I was raised alongside, and it feels like a reunion with a childhood friend. We might not meet often, but when we do, we're at home. I think back to the rules shaping my New York life, and the rigid structure that guarantees the security needed to survive in a place with few second chances. It feels strangely alien to the life I experience fleetingly every winter in Dhaka; and although on most days I rely on this very structure for survival, today it feels unfamiliar, remarkably sterile, like a life seeped in the insipidity of achieving and chasing, lacking any semblance of spirit or joy.

Dhaka is my place of healing. My days start with ripe pomegranates, my mother waiting with a box of motichoor laddoos for us to share over breakfast, and the smell of crisp winter mornings conflated with the unbearable honking of cars doing rounds of school drop-offs. Most days, my mornings bleed into the afternoons, as my parents and I spend endless cups of cha over stories about childhoods, relationships, collective and personal traumas and the love that binds us together. When at home, whether I'm reading, eating, working or daydreaming, my parents and I are always together; the physical proximity they demand of me during my time in Dhaka is a testament to our time apart, and the lives we live away from each other. To my mother, my time at home feels like time borrowed from someone else's life. She needs me in her line of sight at all times. My name, dripped in honey, echoes off the walls when I'm not near her, as if any moment when she cannot see me is a moment of loss. For this, I count my blessings, because where else can I find a love this pure, without questions or conditions, where I'm enough just as I come, and all I have to do is be.

Home is tucked away in the softest corners of Dhaka: it hides in the flavours of Jhorna's aloo bhorta, in Baba's worries that come alive when I oil his hair, in the rings that form inside our cha cups as my friends and I retell stories that have held us together for years, and in the anchol of my dadima's sharee that dances with the jingle of her keys. Dhaka is my place of loss; it is where I come to grieve the parts of my childhood I've lost, and it is where I have buried loved ones who raised me, like my dadima and nanu.

It's my first time home since the passing of dadima, and a visit to her graveside is a reminder of how physical loss is, and the suddenness with which it erases parts of home that were tied to a person and their presence. Her passing looms over my head like a heavy, dark cloud; I think of her love for feeding others – pitted lychees waiting for us after school, pitha in all seasons, jhal aam shotto baking under the winter sun – now there is no one impatiently running after me with a second piece of gorur gosh with a side of folktale: "Take two bites or you'll fall into the river." Her passing has left a void in this city, and parts of my childhood and of life in Dhaka have left with her.

In Dhaka, mourning has dignity, it is patient and empathetic and brings with it the kindness and strength of community. It doesn't come bearing a timeline; there is less of a rush to bounce back into work or society, less of a need to hide your pain, and more room to grieve and tend to a broken heart. You're offered the kindness to take more than you can give. There is grace in healing over time, which is a luxury New York cannot extend me.

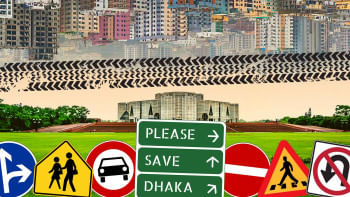

And so, every year, I carry all my love, but more so all my loss to Dhaka; I rely on the generosity of the communities, kindness of strangers, love of childhood friends, and security of family to heal and mourn all I have lost. There's something in Dhaka's air, heavy with its own struggles, frustrations, and heartbreak that hide behind its endless optimism and champion spirit. It becomes your companion during times of anguish and loss, but also teaches you to pick yourself up after a fall, instilling the spirit of fighting, of being fearless.

Dhaka is my place of joy, of hope, and of the kind of love that bursts at the seams. It's the place that has given me friendships of more than 28 years, the comfort and security of which have held and sustained me through the different seasons of my life. Our stories started at the age of three, inside a freshly painted school in the corner of a busy Dhanmondi street; they have travelled through geographies, danced through weddings and held hands through heartbreaks, they have weathered fights and nursed each other's illnesses. All this over hours of retelling the same stories while sharing endless cups of cha, and all this while finding a way back to each other, regardless of where life has taken us. Dhaka feels glorious from the sweetness and secrets of childhood friendships. And today, my home is an extension of these friendships. And every winter, without question or delay, they converge in the heart of my beautiful, broken city.

Winters in Dhaka are a ballad carried from the city's birds to its few remaining trees, from the nonchalance of children playing in parks to the scent of mehedi on brides, from the hustle of street vendors to the buzz of new friendships forming on university campuses. This season is a celebration of the city, both in defiance of its reality and in honour of it. The lights strung in the corners of every street and the smell of kachchi wafting out of the windows mingle with the anticipation of a groom's arrival and the changes about to mark the beginning of a bride's new life. It seems as if the city is the bride, dressed in a red sharee, adorned in traditional gold jewellery that's complete with a teep, she's waiting for a glimpse of her beloved as they embark on this journey, one marked by hints of apprehension, but mainly by hopes and dreams.

Through all the mangoes and monsoons of my life, what has remained constant is the comfort and security of Dhaka. A city that cannot be contained within borders, but lives in the souls of those that carry with them a piece of what it means to be from this unforgettable, extraordinary place. A city of heartache and broken dreams, a city of triumph and soul-crushing defeats, a city that breaks you bone by bone, then nurses you back to health. A city exploding with love and longing. I carry all this with me, and once again prepare to leave the city of my faraway dreams, a home that I remember, not one where I live.

Sara Rashid, based in New York, is interested in how religion and politics shape art in South Asia.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments