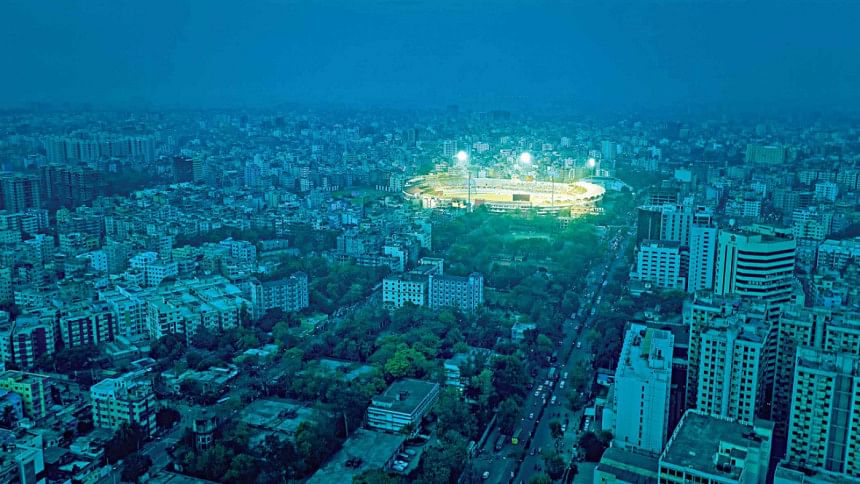

Dhaka is an island

Living within the hullabaloo of the city, in the belly of the beast, so to speak, there is a vital aspect of Dhaka that has become invisible. We can no longer see a city framed and encircled by rivers. How ironic is that! In a nodi-beshtito landscape, the river has disappeared from view. Not quite literally, but perceptually and ideationally. And, often, quite literally. That is, the river is no longer in our minds and is not accessible either. This is not the case for someone living in Paris, Bangkok, or Kolkata. Think of Buriganga, that is, if you can, the banks of which nurtured the beginning and growth of Dhaka. The river is now polluted beyond repair and its banks are almost inaccessible to the general public.

Once upon a time, rivers, wetlands, flood plains and canals used to completely girdle the city in a beautiful tapestry of green and blue. Now, a short ride on any of the rivers of Dhaka will show how that landscape is being mistreated and abused. A couple of days back, a few of us took a boat ride on the Balu River. Other than one or two leisure boats, 90 percent of boats were sand barges slithering on the darkish water for the purpose of filling up nearby wetlands. We found a few instances where the riverbanks were recognised, but mostly it seemed like a long-disowned wasteland. Even such planned enterprises as Purbhacahal and Jolshiri failed to recognise the beauty of the rivers in their grand plans.

I describe this phenomenon, in which the rivers have receded from our lived experience, as the vanishing scope of the city. Accelerated by planning priorities and development drives, and a clear disregard for the virtues of rivers, rivers and a whole ecology associated with them are receding from our urban priorities. This is unequivocally disastrous.

Writing in the book Designing Dhaka in 2012, I proposed the viewpoint that "Dhaka is an island." The architect Muzharul Islam made a similar claim in 1993: "Dhaka has rivers on three sides, and lowland on the other, it is extended along the north-south. It is like an island." The claim is both rhetorical and prospective. It is rhetorical in the sense that Dhaka city is not quite an island but the way it is framed by water on all four sides, it appears to be one. Metropolitan Dhaka and its immediate areas are framed by four rivers—the Buriganga, the Turag, the Balu, and the Shitalakhhya. Like a garland or ring, the four rivers encircle a region on which the historic city of Dhaka originated and developed, and where the expanding footprint of the modern city is fast growing. We calculate that the total linear length of the four riverbanks, considering both sides, is 216 kms!

The historical importance of this "ring of rivers" cannot be overemphasised. British cartographer James Rennell's map of Dhaka clearly showed its location in a riverine geography. Earlier, in the 15th century, the Chinese emissary Ma Huan and his companions travelled up to Sonargaon and Dhaka in their Chinese junks. At the southern tip, Idrakpur Fort was constructed by the Mughals at the perfect location facing the daunting south that brought in marauders and troublemakers. Birulia village, once a hub of commerce, now sits as a desolate island in the river route of the Turag. Jute factories on the Sitalakhhya led Rumer Godden to write her novel The River which became the basis for Jean Renoir's 1951 film of the same name. It was Renoir's film that inspired Satyajit Ray. Such is the web of rivers.

Rivers are not just ribbon-like channels. It also suggests a vast water ecology that includes canals, lakes, wetlands and floodplains that still infiltrate the body of the city. Let us not forget the essence of a river: it is all about flows. The blatant increase in impermeable surfaces and engineered systems have disrupted both flows and absorptions. If we are deleting rivers from our horizon, we are actually nullifying the life-enhancing gift of nature.

Claiming that Dhaka is an island is an earnest call for an ecological and nature-oriented restoration of the city, and to experience, in the words of the Chinese landscape architect and ecological planner Kongjian Yu, the "free, fertile, vigorous and poetic landscape."

By prospective, I mean how we can erect our buildings, infrastructures and cities, that is, a whole new city form, with the rhythm of the river rings. How can we create an active public realm all along the riverbanks? And how can we experience a passenger river route in the ring? There are a few tasks involved here.

The first task is environmental, that is, to retain the rivers as rivers, by cleaning up the rivers, de-polluting them, and maintaining their flow. This is fundamental and there is no two-way about this. The second task is legal, to create distinct policies for the definition and usage of the riverbanks for what happens on riverbanks lead to the eventual deterioration of rivers. Both these tasks are fairly well known in our discourse on rivers, but they have not been able to restore the primacy of those rivers. If policies and outcries will not, what will?

There is a third task that may actually save rivers—we need to show by examples how the rivers and riverbanks can be used. I argue that people abuse the riverbanks when there is no demarcated or defined public realm. Riverbanks are actually a natural public realm. Anyone should be able to reach an urban riverbank, unfettered and unobstructed. And once there, he or she should be able to take in the full glory of a river. A singular and time-tested way to preserve riverbanks is to create unobstructed walkable public spaces along all the riverbanks. Our rural riverbanks are like that but the moment a river enters or passes by a city or town, it immediately becomes an object of abuse in which encroachment and privatisation turn the rivers black and deny the riverbanks to the wider citizens. If any strategy that will save our riverbanks, it is the publicisation of its banks.

It does not take too much to create public spaces along riverbanks. All that is needed is an attention to public access and making simple gathering spaces such as parks, gardens and pathways. Pathways could be for both walking and biking. Ideally, I should be able to walk from Ashulia along the Turag and the Buriganga and reach the southern tip of Narayanganj (we calculated it would take nine hours at 10 minutes/km).

We need to develop a hydrophilic image of the city, where the rivers are passionately loved and used. A civic activism is needed around the primacy of rivers in the life of a city. A map of a city is often a way to iconise that primacy. Such an iconic map of Dhaka is yet to be drawn. We propose a new visualisation of Dhaka in which the ring of rivers is prioritised.

In Kongjian Yu's optimistic view, rivers and civilisations are closely bound up in which the big rivers will continue to nourish human civilisations. "No rivers, no dreams," as he declares. One could add: no dreams, no humanity. In a time of paradoxical development, when industrial growth and technological optimism have wrought havoc on Earth, we need to explore a "nature-based path" for redemption in which the central role is played by the river.

Kazi Khaleed Ashraf is an architect and writer, and directs the Bengal Institute for Architecture, Landscapes and Settlements.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments