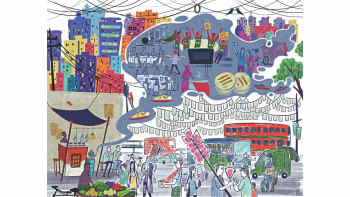

The city is a beautiful thing when it’s for everyone

A city is a web of facilities and opportunities in which different agencies and communities lay stakes, push boundaries, and make bullish claims of making things better. And yet, the discussion on appropriateness and effectiveness continues. Continuing the conversation, I cite five axioms in making a city beautiful, humane, and spirited.

Axiom 1: A beautiful city is made not by beautification, but by the careful process of design, planning, and assembling.

As an architect and urban designer, I have come to question the term "beautification," although "City Beautiful" was a movement in the late-19th-century US to improve civic and social conditions through architecture. In Dhaka, beautification is mostly a beautiful deception, "a practice in which state money is mobilised for an unnecessary project that has little value in public benefit, and often carried out by bureaucratic decisions that lack knowledge of the actual requirements and consequences of what is going on. The work itself, usually not reviewed by any learned body, is carried out by dubious professionals and builders…

"No city planning culture in the world uses the term beautification in the design of their cities; planning proceeds through the methods and techniques of urban design, landscape design or civic design, any of which requires the involvement of trained and dedicated professionals. Only societies afflicted by the Potemkin syndrome put up hideous things – from billboards to bonsai trees – to hide an incompetence, which they then call 'beautification.'"

I wrote the above paragraphs six years ago in response to the strange bonsai planting scheme for Airport Road. The Potemkin phenomenon refers to propping up installations for a quick glory for the benefits of the select few. All that beautification enterprise along that road, dedicated solely for passing vehicles, paid no heed to the pedestrian. For a road with high-speed traffic, there should be barriers, typically with tree canopies and plants, as a buffer against the traffic. The plant landscaping on the far side is an arbitrary and useless spectacle. I describe that as the "fiction of beautification."

Axiom 2: A good city is better than a beautiful city.

A good city is hard to define, and yet being liveable, healthy and equitable are some defining parameters.

Dhaka remains far from the destination of a "good" city. Dhaka is a city of brazen buildings, of opulent and dazzling structures showcasing the new economic clout, and of relentless build-up marking the intense density of the city. Yet, buildings and structures alone do not make a city, far less a good city. Cities need – and Dhaka needs that dearly – various forms of public and civic places that will provide the essential experiential spaces where citizens can arrive and thrive, unfettered, in an urban milieu. Unlike individual buildings which are mostly privatised and secured, public spaces offer an equalitarian experience that any and all can participate in.

The ultimate measure of a good city, and consequently a beautiful city, are the qualities of public spaces. Such spaces signify "commons" or outdoor living rooms that stage the city's life and energy, and make the city inviting for everyone. The global pandemic ushered a new urgency around public health and a strong necessity for such public spaces in the city, whether as plazas, chottors, promenades, fields, and tree-filled parks and gardens. If a plan for Dhaka aspires to be socially inclusive and humanistic, it should begin with a generous attention to creating public spaces at all scales, from the city to the neighbourhood and the corner of a street.

Axiom 3: Parks, playfields, and gardens are not the same thing.

Dhaka has received quite a few designed parks in recent times which, at one level, are a gift to the citizens. Such parks are, at best, rudiments of public spaces in the city in which people can gather for recreation. Yet, there is a lack of landscape intelligence in the making of those parks as they perform mostly as plazas, entertain commercial hubs, and really are playfields. There is hardly a park with a conscious planting of trees and greeneries amid which a visitor may find a respite from his or her life of urban stress.

It appears that people entrusted with the making and administering of parks have not quite clarified a distinction among parks, playfields, and gardens. For a true garden, one should look at Balda Garden. Armanitola School field and Abahani ground are examples of playfields. Ramna Park and Suhrawardy Udyan remain as examples of designated parks. It is critical to study and highlight the performative nature of each of the types.

The climate of Dhaka desires it to be a garden city, a lush green pulsation of life and foliage. The city of Dhaka used to be synonymous with trees – flower-bearing, scent-emanating, and season-marking trees. I still remember the dignified row of shadow-giving, corridor-creating trees along the street in front of Dhaka Medical College. If one were to travel just outside Dhaka, one would notice that there is no square inch that is not green and vegetal in this fecund land. Yet, Dhaka is slowly and surely losing its green and tree coverage.

For a city like Dhaka, so intoxicated with economic returns from every square inch of land, greenery has become an adversary, only to be propped up as tokens in beautification schemes.

Axiom 4: A proper walkable condition is a civic right.

Most beautification efforts are targeted for people in a moving vehicle, in which the fate and state of the poor pedestrian are ignored. An evidence of that is the dedication and passion for constructing road medians. We have calculated that the median on Gulshan Avenue is constructed of so much reinforced concrete that one could build 100 one-storey houses out of them.

It would have been wiser to give more attention to the sidewalk, where people are. If open and public places define the civic realm of a city, sidewalks or footpaths are a necessary component of that network. The sidewalk is actually a linear public space that defines the humanity of any decent city; it belongs to the culture of walking, strolling and promenading, and getting around without hindrances. This is particularly critical for Dhaka where more than 50 percent of the people walk. Such urban pedestrian systems as boulevards, promenades, river walks, or simple sidewalks that are the hallmark of all liveable cities are, for most part, non-existent in Dhaka. And if they do exist, they are in bits and pieces and do not create a legible and defined network.

A proper walkable condition is a civic right.

Axiom 5: Trees are an existential necessity.

Walking brings us to trees. Since humans built the first cities after clearing trees, cities and trees have held a contentious and complicated relationship. From the predominant perspective of Dhaka, a city is most profitable when totally built sans trees, but to be a good city, an equation with trees is necessary.

The purpose of trees in a city is common knowledge: trees provide a green antidote to the stark built-ups both in visual, existential, and psychological terms. Trees absorb pollutants in the air, catch rainwater, and minimise heat. In urban parks and gardens, trees are an ancient foil for human existentiality. Trees on roadsides provide shade-giving canopies for the pedestrian. In the condition of climate change and heat gains, trees have acquired an ethical and existential urgency.

Trees may belong to the realm of the public, but they go missing in the brutal development climate. Ancient trees are uprooted without remorse. Trees are planted where there should have been plants, and vice versa. In most cases, trees and vegetation are planted in a helter-skelter manner without a knowledge of their species, behaviour and purpose. The term "green" is abused, even by professionals. Instead of grass in a field/park, they apply artificial turf and claim "greenness."

There is, as far as we know, no policy, guideline or charter for trees, for their planting, cutting and replanting. Consequently, there is an ad hoc and unilateral manner in doing business in which qualified people are hardly involved and informed decision-making is rarely engaged. If the tree is life, this is serious business.

Kazi Khaleed Ashraf is an architect and urbanist, and directs the Bengal Institute for Architecture, Landscapes and Settlements.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments