The question of translation

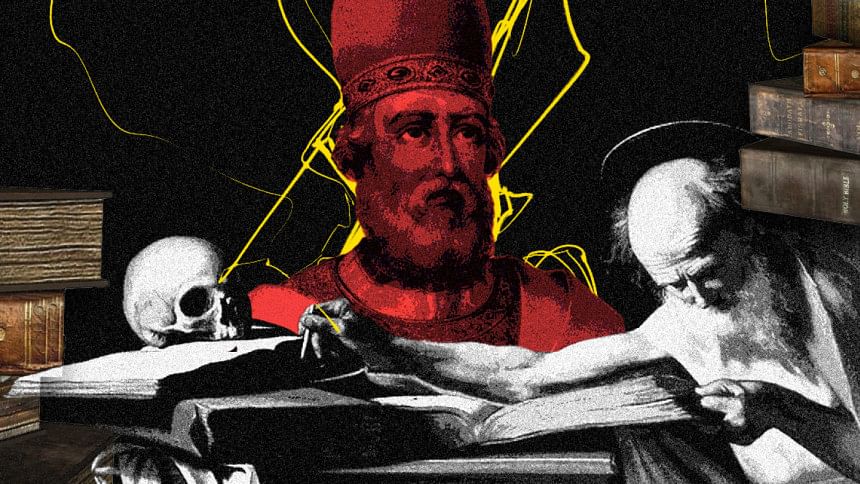

On May 24, 2017, the United Nations General Assembly adopted a resolution declaring September 30 as International Translation Day, commemorating the feast of St Jerome, a multilingual with a mastery of Greek, Hebrew, and Latin, canonised as the "Patron Saint of Translators." He was commissioned by Pope Damasus I in 382 to revise the Latin translations of the Bible by revisiting and reviewing the original texts in Hebrew and Greek (Septuagint) by 404, resulting in the Vulgate Bible, to be officially used by the Roman Catholic Church henceforth.

Suffice it to say, this belated recognition of the translators was long in the making. The International Federation of Translators advocated for marking this day from its very inception in 1953, until its official celebration kicked off in 1991. It was intended as an acknowledgment of the profession, historically instrumental in bringing about a bridging network among an ever-growing number of language communities, cultures, and nations arguably to facilitate meaningful dialogues and public discourses that potentially beef up international cooperation and security, and bolster and enhance alterity, diversity, equity and inclusivity. The essence of this enterprise is captured in the theme of this year's theme for the day: "Translation unveils the many faces of humanity."

Accolades for and invectives/innuendoes against translation were never in short supply. The growth of world culture, the development of comparative literature, and the civilisation in Western Europe were deservedly attributed to the shaping influence of translation. French philosopher Paul Ricoeur (2004) describes the role of a translator as an arbiter, or cultural mediator, imbued with the art and ethics inherent in translation, considered invaluable within the confounding context of unending ethnic and religious conflicts. He argues that translation not only spreads knowledge, but also transforms what it means to know, to the extent that the notion of navigating an increasingly complex world is inconceivable without translation. As millions of people keep moving, migrating and fleeing across the world in the 21st century – more than ever before – for a wide array of variables including, but not limited to, unemployment, underemployment, famines, persecution, natural disasters, environmental calamities, warfare and tourism, prompting displacement or "deterritorialisation," to borrow from Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari (1972), the global significance of translation inexorably springs to the fore.

Nonetheless, a double entendre has always been imputed to translation. The Italian adage, "Traduttore Traditore" or "Translator, Traitor" obtains unabated. The translator, Ricoeur postulates, serves two masters – the foreign author and the reader who speaks the same language as the translator, propelled by the pressing need to appropriate, resulting in the paradox of being "doubly sanctioned" in which the "vow of faithfulness" is undercut by "a suspicion of betrayal." The plight of Afghan translators following an abrupt pull-out of the US from Afghanistan in 2021 epitomises a blatant case in point.

There is no denying the truism that translation historically served the best interest of the colonisers anywhere from intelligence-gathering to sustaining colonial rule through persuasion, knowledge and exoticisation of the colonised "other," by definition without history and unable to represent itself before being rendered (translated, better still) adequately compliant and subservient as a faithful subject to be counted on contemporaneously and prospectively, consistent with the discursive construction and formation underpinning how power is complicit with knowledge. Translations from the non-Western originals to the Western target texts were found replete with deep-seated Orientalism, reflected in their caricature, denigration, distortion, oversimplification, trivialisation, stereotyping, subjugating, subtending, subsuming, and domesticating of the irremediable "other". More to the point, regardless of how translation has been scandalously exploited and sidelined as a discipline and an enterprise, it indefatigably served as a powerful site of resistance by interrogating the contradictions and hypocrisies implicit or explicit in the dominant cultural values and practices, as Lawrence Venuti (1998) so cogently argued.

Translation not only spreads knowledge, but also transforms what it means to know, to the extent that the notion of navigating an increasingly complex world is inconceivable without translation.

The search for the holy grail of perfect translation from the source language to the target language has been likened by Walter Benjamin to the "messianic echo" of the original. In spite of its inevitable pathways of digression/dispersion/dissonance/distortion, translation tends to (re)constellate into an afterlife or incarnation of the original text at best. In other words, translation embarks on an intercultural and intertemporal endeavour, bearing the trace of the original, carried over to the present through metamorphosis. In Benjamin's own words, translated from the German original (as mise en abyme), the translator's task is "to find the intention towards the language into which the work is to be translated, on the basis of which an echo of the original can be awakened in it."

In this process, the survival or afterlife of the original text hinges on the transitional space between the two languages/cultures, generating hybridity, analogous to the "international space of discontinuous historical realities" (Bhabha, 1994:217), requiring iterative disambiguation. "It is not about the passage from one language to another, but about the crossing of a threshold characterised by blurred limits," suggests Maria Teresa Costa (2022, Pg 17-18). The putative echo turns out to be "a complex figure of resonance that cannot be reduced to the repetition of a stable entity" (Pg 216).

Derrida's rereading of Benjamin reduces the text's survival, or afterlife, through translation into one "living on the boundary, on borderlines, on the edge" (Bassnett, 2013, Pg 342). It resonates with Hans-Georg Gadamer's (1989) framing of translation that dispenses with the original's reproduction by embracing empathy and distance. Ricoeur treads the fine line to posit that "a fantasy of perfect translation takes over from... (the) banal dream of the duplicated original" (Pg 5). Extending the dialogic underpinning of Gadamer's hermeneutics, Ricoeur also comes up with a heterodox exegesis that "the self only knows itself through the other." In this hermeneutics of selfhood, oneself is understood as both selfhood and an(other), adding to the problematics of the illusory origin associated with translation.

This is an excerpt from a larger article.

Faridul Alam teaches at the City University of New York.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments