Will we ever get the Teesta back?

Water is the lifeblood of our planet—fundamental for life; essential for economic growth, food production, and human survival; but also a source of conflict and/or cooperation. Water flows across national borders in the form of rivers, lakes, and groundwater which connect nations, ecosystems, and humans. Several water-related disputes have erupted throughout human history fueling conflicts as well as promoting cooperation. As far back as in 2500 BC, there was a treaty between the Sumerian city-states of Lagash and Umma that came to an agreement to resolve a water dispute along the Tigris River. Realising the critical role that water plays in establishing global peace, stability, and prosperity, the theme set for World Water Day 2024 is "Water for Peace."

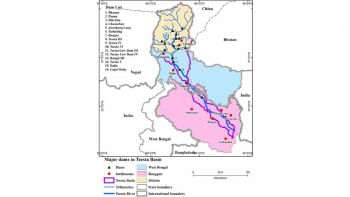

The Teesta is an international river shared by Bangladesh and India. It originates in Sikkim, flows through West Bengal, and joins the Brahmaputra River (known as the Jamuna in Bangladesh) before eventually flowing into the Bay of Bengal. Teesta is critical to the lives of over 30 million people in Bangladesh and India, who rely on its water for irrigation, drinking, fishing, energy, and other agricultural and domestic purposes. The signing of the Teesta Water Sharing Agreement between India and Bangladesh has been a contentious issue for long. After several years of negotiation, the two countries reached an agreement under which Bangladesh would receive 37.5 percent of the Teesta's waters, while India would get 42.5 percent, and the remaining 20 percent would be reserved for environmental purposes.

The Teesta treaty was close to being signed during the then Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh's visit to Bangladesh in 2011. However, the process was stalled due to opposition from the West Bengal government. Since then, the treaty has been in a deadlock. Narendra Modi's government also committed to signing the accord several times. During his first visit to Bangladesh in 2015, Modi said, "Our rivers should nurture our relationship, not become a source of discord…Water sharing is, above all, a human issue…I am confident that with the support of state governments in India, we can reach a fair solution on Teesta and Feni Rivers." Despite Bangladesh's continuous efforts, the issue has remained unresolved for decades, which has become a major source of frustration between the people of the two neighbouring countries.

Teesta is the fourth largest river in Bangladesh, entering the country through Rangpur division, northern part of Bangladesh. Teesta's floodplain covers 2,750 square kilometres, supporting diverse flora and fauna, ecosystems, and the livelihoods of millions of people. The people rely on Teesta for agriculture, food production, fishing, other domestic needs and earning livelihoods. It is the primary source of water for the cultivation of Boro rice—Bangladesh's largest crop—and irrigates approximately 14 percent of the total cropped area. The Teesta is the main source of irrigation for the northern region of the country, which is known as the granary of Bangladesh. The Teesta Barrage Project, the largest irrigation project in Bangladesh, uses water from the Teesta River to irrigate about 540,000 hectares. Its command area consists of 750,000 hectares and includes parts of seven districts: Nilphamari, Rangpur, Dinajpur, Bogura, Gaibandha, and Joypurhat.

All this aside, the flow of Teesta River in Bangladesh has declined significantly due to the development of various infrastructures in the upstream areas of India, including dams, barrages, and hydropower structures. While these infrastructures have increased water availability in India, they have also disrupted the flow and altered the natural hydrological regime, affecting water availability downstream in Bangladesh. According to a study conducted by the Bangladesh Water Development Board, the average annual flow of the Teesta at the border point of Dalia was 6,710 cusecs (cubic feet per second) prior to the construction of the Gazaldoba barrage in West Bengal, India which decreased to 2,000 cusecs after the barrage went into operation in 1995. The minimum flow during the lean season dropped from 1,500 cusecs to as low as 200-300 cusecs, which is far below the required level. The groundwater level in the Teesta basin has dropped by about 10 metres over the last decade due to reduced surface water flow and increased use of groundwater for irrigation.

The inadequate and erratic flow of the Teesta River during the dry season has adversely affected the crop yield, particularly the Boro rice. According to a study by the International Food Policy Research Institute, the Teesta water shortage has resulted in a loss of about 1.5 million tons of Boro rice production per year, which is equivalent to about nine percent of the country's total rice production. The study also projected that the Teesta water shortage could reduce the country's rice production by about eight percent by 2030, and by about 14 percent by 2050, under a business-as-usual scenario. Water scarcity in Teesta basin increases production costs and risks for farmers as well as leads to social problems like migration, displacement, poverty, inequality, and violence among water users and stakeholders.

Bangladesh and India have been enjoying a historic period of good relations and have a history of resolving bilateral issues peacefully and amicably. Both the countries signed the Ganges Water Sharing Treaty in 1996, which addressed the long-standing dispute over the sharing of water resources of the Ganges River during the dry season. In 2014, the two countries resolved their maritime boundary dispute through arbitration under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. Both countries accepted the verdict, paving the way for greater cooperation in energy, fisheries, and maritime security. In 2015, the two countries signed a historic land boundary agreement that resolved decades-old border disputes and exchanged enclaves, putting an end to the plight of thousands of stateless people. Recently, the countries have signed a Memorandum of Understanding on interim water sharing of the Kushiyara River, which allows India to withdraw 1.82 cusecs of water from the Feni River to meet the drinking water needs of Sabroom town in Tripura, which has been facing water scarcity. Both the countries are also deepening economic cooperation including trade, transit, and energy cooperation.

Resolving the Teesta Water Accord is about more than just a water issue; it is about fostering trust, peace, harmony, and sustainable development. A successful Accord on the Teesta would foster mutual confidence encouraging further collaboration on shared challenges including energy security, environmental management, flood protection and development of transboundary water resources including mutually beneficial projects on shared water resources with provision of a legal framework. As the climate change affects adversely the future water availability and increases further demand for water in the countries, a longer-term water solution depends on the collaborative development of transboundary water resources, building reservoirs in the upstream of the Teesta in Sikkim, and using and managing the reserved water for mutual benefit in an agreed and cooperative manner. Thus, India and Bangladesh must collaborate to find a mutually acceptable long-term solution to the Teesta water-sharing issue, guided by international water law principles and a spirit of long-standing friendship and cooperation.

Golam Rasul, PhD is professor in the Department of Economics at International University of Business Agriculture and Technology. Reach him at [email protected]

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments